P.O. SEVAGRAM, DIST.WARDHA 442102, MS, INDIA. Phone: 91-7152-284753

FOUNDED BY MAHATMA GANDHI IN 1936

ARTICLES : Relevence of Gandhi

Read articles written by very well-known personalities and eminent authors about their views on Gandhi, Gandhi's works, Gandhian philosophy and it's relevance today.

ARTICLES

Relevance of Gandhi

- Ibu Gedong Bagoes Oka - A Study of Gandhian Influence in Indonesia

- Global Peace in the Twenty First Century: The Gandhian Perspective

- Relevance of Gandhi in Modern Times

- Gandhi is Alive and Still Relevant

- Taking up Sarvodaya As Our Duty

- Gandhi Will Live On

- Mahatma Gandhi Today

- The Influence of Mahatma Gandhi

- Gandhi's Message and His Movement 50 Years Later

- The Relevance of Gandhi

- Good Bye Mr. Gandhi- Awaken Thy Moral Courage

- Relevance of Gandhian Ideals In The Scheme of Value Education

- Gandhi And The Twenty First Century Gandhian Approach To Rural Industrialization

- Gandhi's Role And Relevance In Conflict Resolution

- Gandhi In Globalised Context

- The Gandhian Alternatives And The Challenges of The New Millennium

- Gandhian Concept For The Twenty First Century

- Champions of Nonviolence

- Science And Technology In India: What Can We Learn From Gandhi?

- Passage From India: How Westerners Rewrote Gandhi's Message

- Time To Embark On A Path To New Freedom

- Increasing Relevance of The Mahatma

- Gandhi's Challenge Now

- The Legacy of Gandhi In The Wider World

- Quintessence of Gandhiji's Thought

- Recalling Gandhi

- Mohandas Gandhi Today

- The Relevance of Gandhian Satyagraha in 21st Century

- Relevance of Non-Violence & Satyagraha of Gandhi Today

- India, Gandhi And Relevance of His Ideas In The New World

- Relevance of Gandhi's Ideas

- The Influence of Mauritius on Mahatma Gandhi

- Why Gandhi Still Matters

- The Challenge of Our Time: Building Sustainable Communities

- What Negroes Can Learn From Gandhi

- Relevance of Gandhi

- Towards A Non-violent, Non-killing And Peaceful World : Lessons From Gandhi

- Gandhian Perspective on Violence And Terrorism

- GANDHI - A Perennial Source of Inspiration

- An Observation on Neo-modern Theories of Global Culture

- The Techno-Gandhian Philosophy

- Global Peace Movement and Relevance of Gandhian View

- Technology : Master or Servant?

- Gandhis of Olive Country

- Gandhian Strategy

- The Effect of Mass Production and Consumerism

- Gandhi's Relevance Is Eternal And Universal

- Service To Humanity

- Relevance of Gandhi: A View From New York

- Gandhi And Contemporary Social Sciences

- India After The Mahatma

- Pax Gandhiana : Is Gandhian Non-Violence Compatible With The Coercive State?

- GANDHI : Rethinking The Possibility of Non-Violence

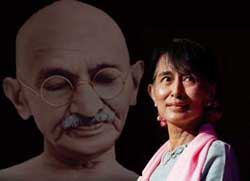

- Aung San Suu Kyi : In Gandhi's Footsteps

- Gandhi: Call of The Epoch

- Localization And Globalization

- Significance of Gandhi And Gandhism

- Understanding GANDHI

- Gandhi, Peace And Non-violence For Survival of Humanity

Further Reading

(Complete Book available online)- Why Did Gandhi Fail?

from GANDHI - His Relevance For Our Times - Gandhi's Political Significance Today

from GANDHI - His Relevance For Our Times - India Yet Must Show The Way

from GANDHI - His Relevance For Our Times - The Essence of Gandhi

from GANDHI - His Relevance For Our Times - The Impact of Gandhi on U. S. Peace Movement

from GANDHI - His Relevance For Our Times

Aung San Suu Kyi : In Gandhi's Footsteps

Dr. Anupma Kaushik

Associate Professor, Banasthali University, Rajasthan, India.

Introduction : Her life and family

Aung San Suu Kyi was born on 19 June 1945 in Rangoon. She derives her name from three relatives. Aung San from her father, Suu from her paternal grandmother and Kyi from her mother Khin Kyi. She is frequently called Daw Suu by the Burmese or Amay Suu, i.e. Mother Suu by some followers. (Gandhi was called Bapu by his followers) Suu Kyi is the third child and only daughter of Aung San considered to be the father of modern-day Burma. Her father founded the modern Burmese army and negotiated Burma's independence from the British Empire in 1947 but was assassinated by his rival in the same year. She grew up with her mother, Khin Kyi and two brothers, Aung San Lin and Aung San Oo, in Rangoon. Aung San Lin died at age eight, when he drowned in an ornamental lake on the grounds of the house. Her elder brother immigrated to San Diego, California, becoming a United States citizen. After Aung San Lin's death, the family moved to a house by Inya Lake where Suu Kyi met people of very different backgrounds, political views and religions. She was educated in Methodist English High School for much of her childhood in Burma, where she was noted as having a talent for learning languages.1

Suu Kyi's mother gained prominence as a political figure in the newly formed Burmese government. She was appointed Burmese ambassador to India in 1960, and Aung San Suu Kyi followed her there, she studied in the Convent of Jesus and Mary School, New Delhi and graduated from Lady Shri Ram college in New Delhi with a degree in politics in 1964. Suu Kyi continued her education at St Hugh’s college, Oxford obtaining a B.A. degree. After graduating, she lived in New York City and worked at the United Nations primarily on budget matters for three years. In late 1971, Aung San Suu Kyi married Michael Aris, a scholar of Tibetan culture living in Bhutan. The following year she gave birth to their first son, Alexander Aris in London; their second son, Kim, was born in 1977. Subsequently, she earned a PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London in 1985. She was elected as an Honorary Fellow in 1990. For two years she was a Fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies (IIAS) in Shimla, India. She also worked for the government of the Union of Burma.2

In 1988 Suu Kyi returned to Burma, at first to tend for her ailing mother but later had to lead the pro-democracy movement. Aris' visit in Christmas 1995 turned out to be the last time that he and Suu Kyi met, as Suu Kyi remained in Burma and the Burmese dictatorship denied him any further entry visas. Aris was diagnosed with cancer in 1997 which was later found to be terminal. Despite appeals from prominent figures and organizations, including the United States, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan and Pope John Paul II, the Burmese government would not grant Aris a visa saying that they did not have the facilities to care for him, and instead urged Aung San Suu Kyi to leave the country to visit him. She was at that time temporarily free from house arrest but was unwilling to depart, fearing that she would be refused re-entry if she left, as she did not trust the military junta’s assurance that she could return. Aris died on his 53rd birthday on 27 March 1999. Since 1989, when Aung San Suu Kyi was first placed under house arrest, she had seen her husband only five times, the last of which was for Christmas in 1995. She was also separated from her children, who live in the United Kingdom, but starting in 2011, they have visited her in Burma.3

Political Life, Vision and Influences

Coincident with Aung San Suu Kyi's return to Burma in 1988, the long-time military leader of Burma and head of the ruling party General Ne Win, stepped down. Mass demonstrations for democracy followed that event on 8 August 1988 (8–8–88, a day seen as auspicious), which were violently suppressed in what came to be known as the 8888 Uprising. On 26 August 1988, she addressed half a million people at a mass rally in front of the Shwedagon Pagoda in the capital, calling for a democratic government. However in September, a new military junta took power.4

Aung San Suu Kyi founded her party National League for Democracy (NLD) on 27 September 1988.5 She serves as its General Secretary. In the 1990 general elections, the NLD won 59% of the national votes and 81% (392 of 485) of the seats in Parliament, although she herself was not allowed to stand as a candidate in the elections and was detained under house arrest before the elections. Some claim that Aung San Suu Kyi would have assumed the office of Prime Minister, however, the results were nullified and the military refused to hand over power, resulting in an international outcry.6

She was awarded the Nobel Peace prize in 1991 for her non-violent struggle for democracy and human right. She used the Nobel Peace Prize's 1.3million USD prize money to establish a health and education trust for the Burmese people. Around this time, Suu Kyi chose non violence as an expedient political tactic. To quote her: "I do not hold to non-violence for moral reasons, but for political and practical reasons". However, non violent action as well as civil resistance in lieu of armed conflict is also political tactics in keeping with the overall philosophy of her Theravada Buddhist religion. She is influenced by both Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of non violence and also by Buddhist concepts. Her aim in politics is to work for democratization of Burmese political system.7 She believes that democratic institutions and practices are necessary for the guarantee of human rights and for was a free, secure and just society where Burmese people are able to realize their full potential.8

One of her most famous speeches are "Freedom from Fear", which began: It is not power that corrupts, but fear. Fear of losing power corrupts those who wield it and fear of the scourge of power corrupts those who are subject to it. She also believes fear spurs many world leaders to lose sight of their purpose. She once said, "Government leaders are amazing, so often it seems they are the last to know what the people want."9

Her party advocates a non-violent movement towards multi-party democracy in Burma, which is under military rule from 1962. Her party also supports human rights (including broad-based freedom of speech), the rule of law, and national reconciliation. In a speech of 13 March 2012, Suu Kyi demanded, in addition to the above, independence of the judiciary, full freedom for the media, and increasing social benefits to include legal aid. She also demanded amendments to the constitution of 2008, drafted with the input of the armed forces. She stated that its mandatory granting of 25 per cent of seats in parliament to appointed military representatives is undemocratic.10 She also favors safeguarding the rights of ethnic minorities in a real democratic union based on equality, mutual respect and trust.11

In 2001, the Burmese government permitted NLD office branches to re-open throughout Burma and freed some imprisoned members. In May 2002, NLD's General Secretary, Aung San Suu Kyi was again released from house arrest. She and other NLD members made numerous trips throughout the country and received support from the public. However, on their trip to Depayin township in May 2003, dozens of NLD members were shot and killed in a government sponsored massacre. It's General Secretary, Aung San Suu Kyi and her deputy, U Tin Oo were again arrested. From 2004, the government prohibited the activities of the party. In 2006, many members resigned from NLD, citing harassment and pressure from the Armed Forces. The NLD boycotted the general elections held in November 2010 because many of its most prominent members including Suu Kyi were barred from standing. The laws were written in such a way that the party would have had to expel these members in order to be allowed to run. This decision, taken in May, led to the party being officially banned. The election was won in a landslide by the military-backed Union Solidarity and development Association (USDP) and was described by US President Barrack Obama as "stolen".122

Discussions were held between Suu Kyi and the Burmese government during 2011, which led to a number of official gestures to meet her demands. In October, around a tenth of Burma's political prisoners were freed in an amnesty and trade unions were legalized. On 18 November 2011, following a meeting of its leaders, the NLD announced its intention to re-register as a political party in order contest 48 by-elections necessitated by the promotion of parliamentarians to ministerial rank.13 In April 2012 she was elected to the Pyithu Hluttaw, the lower house of the Burmese parliament, representing the constituency of Kawhmu. Her party also won 43 of the 45 vacant seats in the lower house and she became the leader of opposition in the lower house.14

Fearless Non-violence against violence

Aung San Suu Kyi had to face an opposition which was much stronger in comparison to her in brute force, as it consisted of the might of the government of Burma. They tried to scare her and her supporters in all possible ways. On 9 November 1996, the motorcade that she was traveling in with other leaders of her party National League for Democracy like Tin Oo and U Kyi Maung, was attacked in Yangon. About 200 men swooped down on the motorcade, wielding metal chains, metal batons, stones and other weapons. The car that Aung San Suu Kyi was in had its rear window smashed, and the car with Tin Oo and U Kyi Maung had its rear window and two backdoor windows shattered. It is believed the offenders were members of the USDA who were allegedly paid 500 kyats (@ USD $0.5) each to participate. The NLD lodged an official complaint with the police, and according to reports the government launched an investigation, but no action was taken. On 30 May 2003 in an incident similar to the 1996 attack on her, a government-sponsored mob attacked her caravan in the northern village of Depayin, murdering and wounding many of her supporters. Aung San Suu Kyi fled the scene with the help of her driver, Ko Kyaw Soe Lin, but was arrested upon reaching Ye-U. The government imprisoned her at Insein prison in Rangoon. After she underwent a hysterectomy in September 2003, the government again placed her under house arrest in Rangoon.15

Aung San Suu Kyi has been placed under house arrest for 15 of the past 21 years, on different occasions, since she began her political career, during which time she was prevented from meeting her party supporters and international visitors. The Burmese government detained and kept Suu Kyi imprisoned because it viewed her as someone "likely to undermine the community peace and stability" of the country, and used both Article 10(a) and 10(b) of the 1975 State Protection Act (granting the government the power to imprison people for up to five years without a trial), and Section 22 of the "Law to Safeguard the State Against the Dangers of Those Desiring to Cause Subversive Acts" as legal tools against her. She continuously appealed her detention, and many nations and figures continued to call for her release and that of 2100 other political prisoners in the country. Suu Kyi was also accused of tax evasion for spending her Nobel Prize money outside of the country. In an interview, Suu Kyi said that while under house arrest she spent her time reading philosophy, politics and biographies that her husband had sent her. The media were also prevented from visiting Suu Kyi, as occurred in 1998 when journalist Maurizio Giuliano, after photographing her, was stopped by customs officials who then confiscated all his films, tapes and some notes. In contrast, Suu Kyi did have visits from government representatives and foreign dignitaries and her physician. She had periods of poor health and as a result was hospitalized. On second May 2008, after cyclone Nargis hit Burma, Suu Kyi lost the roof of her house and lived in virtual darkness after losing electricity in her dilapidated lakeside residence. She used candles at night as she was not provided any generator set.16

On third May 2009, an American man, identified as John Yettaw, swam across Inya lake to her house uninvited and was arrested when he made his return trip three days later. On thirteenth May, Suu Kyi was arrested for violating the terms of her house arrest because the swimmer, who pleaded exhaustion, was allowed to stay in her house for two days before he attempted the swim back. Suu Kyi was later taken to Insein prison, where she could have faced up to five years confinement for the intrusion. The trial of Suu Kyi and her two maids began. During the ongoing defense case, Suu Kyi said she was innocent. The defense was allowed to call only one witness (out of four), while the prosecution was permitted to call fourteen witnesses. The court rejected two character witnesses, NLD members Tin Oo and Win Tin, and permitted the defense to call only a legal expert.17

Despite all of the horrors she has been through, she is neither bitter nor an angry person. She acknowledges that the teachings of Buddhism do affect the way she thinks and clarifies that when she started out in politics, in the movement for democracy, she started out with the idea that this should be a process that would bring greater happiness, greater harmony and greater peace to her nation. And this cannot be done if she was going to be bound by anger and by desire for revenge. So she never thought that the way to go forward was through anger and bitterness, but through understanding, trying to understand the other side, and through the ability to negotiate with people who think quite differently from you and to agree to disagree if necessary and to somehow bring harmony out of different ways of thinking.18

National and International Support

Suu Kyi’s and her party’s massive victories in all the elections have shown how popular she is in her multi ethnic country. One remarkable feature of her political campaign has been the appeal she had for the country's various ethnic groups, traditionally at odds with each other.19

Suu Kyi received immense support from international community. She was given the Rafto Prize by Norway; the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought by European parliament; the Nobel Peace Prize; the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding by India; the International Simon Bolivar Prize by Venezuela; Honorary Citizenship by Canada; and the Wallenberg Medal by University of Michigan.20

The United Nations (UN) has attempted to facilitate dialogue between the government and Suu Kyi. However on the results from the UN facilitation have been mixed. Razali Ismail, UN special envoy to Burma, met with Aung San Suu Kyi but resigned from his post the following year, partly because he was denied re-entry to Burma on several occasions.21

The UN has called upon the Burmese government to release Suu Kyi many a times along with other world leaders, nations and organizations. United Nations Working Group for Arbitrary Detention published an opinion that Aung San Suu Kyi's deprivation of liberty was arbitrary and in contravention of Article 9 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights 1948, and requested that the authorities in Burma set her free, but the authorities ignored the request.22

There have been demonstrations in support in various places in the world and she has received vocal support from the world like the European Union, USA, Australia, India, Israel, Japan, the Philippine, South Korea, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore. Nobel laureates like Desmond Tutu, the Dalai Lama, Shirin Ebadi, Adolfo Perez Esquivel, Mairead Corrigan, Rigobert Menchu, Elie Wiesel, Barrack Obama, Betty Williams, Jody Williams, and Jimmy Carter have supported her.23

The Burmese government could resist the pressure of the international community due to the support from China. To illustrate the US-sponsored United Nations Security Council resolution condemning Burma as a threat to international security, was defeated because of strong opposition from China, which has strong ties with the military junta. China later voted against the resolution, along with Russia and South Africa.24

Burma's relaxing stance, in recent times, such as releasing political prisoners, was influenced in the wake of successful recent diplomatic visits by the US and other democratic governments, urging or encouraging the Burmese towards democratic reform. The Japanese government which spent 2.82billion yen in 2008 and has promised more Japanese foreign aid to encourage Burma to release Aung San Suu Kyi in time for the elections; and to continue moving towards democracy and the rule of law. The New York Times suggested that the military government may have released Suu Kyi because it felt it was in a confident position to control her supporters after the election.25

Suu Kyi and Gandhi

Suu Kyi has herself clearly indicated the sources of her inspiration: principally Mahatma Gandhi but also her father and her religion. Her father too was an admirer of Gandhi although she was not always uncritical of Gandhi.26 There are striking similarities between Suu Kyi and Gandhi. Both loved their country and countrymen so much that they dedicated their lives to their respective countries. Both had to sacrifice their family and professional lives for their cause. Both were imprisoned for long periods by their opposition. Their opposition in both cases were/ are militarily much stronger but morally much weaker. However in both cases the opposition had respect for the two individuals. Both were educated in India and UK and could communicate well in English. Both are revered by their countrymen and respected by the international community. However they are much more similar in their thinking as both share belief in positive energy of courage, peace and non violence by overcoming negative energies such as fear and anger. Both inspire a sense of confidence and hope in the fight for peace and justice. Both symbolize what humankind is seeking and mobilize the best in their followers. They unite deep commitment and tenacity with a vision in which the end and the means form a single unit. It's most important elements are: democracy, respect for human rights, reconciliation between groups, non-violence, and personal and collective discipline. Both believe in human dignity and went a long way towards showing how such a doctrine can be translated into practical politics. Both practiced what they preached: fearlessness. There are many examples of fearlessness shown by Gandhi and Suu Kyi. Gandhi had said that a satyagrahi bids goodbye to fear and practiced it all his life.27 One such occasion, where Suu Kyi, showed remarkable fearlessness was in 1988, when despite opposition by the government, Aung San Suu Kyi went on a speechmaking tour throughout the country. She was walking with her associates along a street, when soldiers lined up in front of the group, threatening to shoot if they did not halt. Suu Kyi asked her supporters to step aside, and she walked on. At the last moment the major in command ordered the soldiers not to fire. Both also stand for a positive hope and give humanity confidence and faith in the power of good.28 Gandhi has inspired Suu Kyi and many others all over the world29 and Suu Kyi is doing the same- inspiring many all over the world.

References

- Aung San Suu Kyi, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aung_San_Suu_Kyi, Accessed on 25.7.2012.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- National League for Democracy, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_League_for_Democracy, Accessed on 29.7.2012.

- Aung San Suu Kyi, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aung_San_Suu_Kyi, Accessed on 25.7.2012.

- Ibid

- Peter Beaumont, Aung Sang Suu Kyi accepts Nobel peace prize, The Guardian, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jun/16/aung-san-suu-kyi-nobel-peace-prize, Accessed on 31.7.12.

- Aung San Suu Kyi, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aung_San_Suu_Kyi, Accessed on 25.7.2012.

- National League for Democracy, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_League_for_Democracy, Accessed on 29.7.2012.

- By Soe Than Lynn, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi urges legislation for ethnic equality, The Myanmar Times.com, Volume 32, No. 637, July 30 - August 05, 2012 http://www.mmtimes.com/2012/news/637/news63708.html, Accessed on 31.7.12.

- National League for Democracy, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_League_for_Democracy, Accessed on 29.7.2012.

- Ibid

- Aung San Suu Kyi, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aung_San_Suu_Kyi, Accessed on 25.7.2012.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Sally Quinn, Aung San Suu Kyi: Buddhism has influenced my world view, the Washington Post, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/under-god/post/aung-san-suu-kyi--buddhism-has-influenced-my-worldview/2011/12/01/gIQAR9m5GO_blog.html, Accessed on 31.7.22012.

- Award ceremony speech, http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1991/presentation-speech.html, Accessed on 31.7.12.

- Aung San Suu Kyi, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aung_San_Suu_Kyi, Accessed on 25.7.2012.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma and India: Some Aspects of Intellectual Life Under Colonialism, Allied Publisher, New Delhi, p 58.

- Lois Fisher, The Life of Mahatma Gandhi,Bhartiya Vidya Bhawan, Mumbai, 2003, p 101.

- Award ceremony speech, http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1991/presentation-speech.html, Accessed on 31.7.12.

- David Hardiman, Gandhi in His Times and Ours, Permanent Blacks, Delhi, 2003, p 238.