P.O. SEVAGRAM, DIST.WARDHA 442102, MS, INDIA. Phone: 91-7152-284753

FOUNDED BY MAHATMA GANDHI IN 1936

Short Stories For Everyone

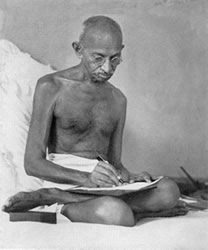

Inspiring incidents from Gandhiji's Life: Selected from the book Everyone's Gandhi

(For the children in the age group of 10 to 15 years)

SHORT STORIES FOR EVERYONE

Gandhi's inspiring short stories selected from the book Everyone's Gandhi

Editor by : Rita Roy

Table of Contents

- All for A Stone

- A Car And A Pair of Binoculars

- My Master's Master

- Enter The Monkeys

- Premchand Quits His Job

- Returning His Medals

- Basic Pen

- Prisoner No. 1739

- Gandhi's White Brother

- Who Saw Gandhi?

- An Early School

- An Unusual March

- Spiritual Heir

- The Less You Have The More You Are

- An Old Goat Talks

- The Phoenix Settlement

- Gandhi in Amsterdam

- Something To Be Shy About?

- Gandhiji The Matchmaker

- Gandhi's Army

- Dandi Snippet

- Hiding Something

- The Image Maker

- Creative Reader

- Postcards To The Rescue

- A Non-violent Satyagraha 214 Years Ago

- Gandhi And Delhi

- Gandhiji's Constructive Programme

- Gandhi Looks At Leprosy

- Baba Amte

- They Gave Peace A Chance

- From Mahatma To God

- Customs Are Out of Fashion

- The Man 'Charlie' Wanted To Meet

- It Came Naturally To Him

- Crossing The Sea of Narrow-Mindedness

- Wear Clothes As They Should Be Worn

- Education: For Life, Through Life

- The Abode of Joy

- To Cling to A Belief

- The Fruit of A Child's Labour

- An Ideal Prisoner

- How A Film Became Something More

- Gandhi: Beyond India

- Gandhi's Life-Saving Medicine

- Understanding The Mechanics of Life With Gandhi

- The Lokmanya and The Mahatma

- Man's Gift To Nature

- Gurudev And His Mahatma

- One-man Boundary Force

- What Does Mahatma Gandhi's Message Mean To Me?

- Let's Play Together

- Children's Response To Conflict

- Beggar By Choice

- The Better Half

- Uncle Gandhi

- The Watch: An Instrument For Regulating Life

- Light The Lamp of Your Mind

- Gandhi's Bet!

- Gandhi Feeling At Home In The Kitchen

- What Is Simplicity?

- Bapu And The Sardar

- The Power of Quality

- Gandhi: The Teenager!

Chapter 51: What Does Mahatma Gandhi's Message Mean To Me?

Susanne Schweitzer

Does Mahatma Gandhi's message have any relevance for young people in the modern industrialized West today? To commemorate the 125th Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi an essay competition was organised for high school students in Germany. This is the prize winning essay.

Six months ago a good friend of mine was murdered. Daniel was brutally stabbed 35 times by two boys of his age simply for the fun of it. The murder was committed without any motive whatsoever, not because the boys felt threatened or had had a quarrel; no, it was a totally arbitrary act.

After the two culprits had been caught my first thought was simply hatred. Pure hatred and the feeling that the bloody deed should be avenged in an equally bloody manner. In my mind hatred almost prevailed over grief, and my anger knew no limits. My sister, Sonja, then gave me Mahatma Gandhi's book "Worte des Friedens" (Words of Peace). I had often heard the name of Gandhi. After all, the man who liberated India is well known, but I had never really taken an interest in Gandhi. I thought the film about him was very good and I was impressed by the way he "fought" against the British, but it all seemed so remote to me: he was an exemplary historic figure.

However, in the days following the murder I got to know quite a different aspect of Gandhi. A few sentences of his made me think: "I hold myself to be incapable of hating any being on earth. By a long course of prayerful discipline, I have ceased for over forty years to hate anybody. I know this is a big claim. Nevertheless, I make it in all humility. To see the universal and all-pervading spirit of Truth face to face one must be able to love the meanest of creation as oneself." I was familiar with such sentences from the Bible, but Mahatma Gandhi made them more vivid and relevant to my life than ever before. From his life one can learn that it is indeed possible to love even one's worst enemy. Gandhi had to suffer humiliation in both South Africa and India. In South Africa he was insulted, abused, spat at and beaten by officials. He did not even try to resist, but bore everything with a smile and an iron will to change this misconduct by non-violent means. Despite all the humiliation, Gandhi remained in South Africa in order to use his legal knowledge to champion the cause of the Indian immigrants in South Africa. "It has always been a mystery to me how men can feel themselves honoured by humiliation of their fellow-beings." Gandhi remained in South Africa to uncover the secret to stop people from making life difficult for one another by making cruel and taunting remarks.

If I apply Mahatma Gandhi's behaviour, the way he dealt with his enemies, to my situation today, it would mean not hating Daniel's murderers but persuading them to mend their ways. Thoughts of revenge would be taboo. I do not succeed in doing this, however often I hear Mahatma's words and concentrate on them.

I would like to be able to live as he lived. I would like to renounce violence and always be kind to everyone. It is not possible. In this situation in particular I have had to concede time and again that it is not possible. Not yet possible?

I feel hatred and want to pay the culprits back two or threefold for the thirty-five stab wounds they inflicted on Daniel.

Martin Luther King once said that Gandhi was inevitable, if humanity was to make progress. He had lived, taught and acted, inspired by a vision of humanity which was developing into a world living in freedom and harmony. We could ignore him, King continued, at our peril.

I agree: Gandhi was inevitable so that the idea of non-violent resistance could be put into practice at least once. Yet today it seems as if Mahatma had never lived, as if scenes like the demonstration in front of Dharasana saltworks had never occurred.

If today one imagines 2,500 men, supporters of one man's ideas, enduring such brutality without even trying to resist their tormentors with force, one has some idea of what Gandhi set in motion in people's hearts and minds at that time. In today's world it is no doubt more the principle of "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth" which prevails.

So should we ignore Mahatma Gandhi? Or is it simply not possible to live together peacefully in this age of competition and rivalry?

However, in my view many people do have a vision of humanity which is developing into a world living in harmony and peace. Yet is it very difficult to lead a non-violent life. Incidents occur time and again at demonstrations which are intended to be peaceful. Suddenly tension escalates. People begin to panic, stones are thrown, policemen attack the crowd with truncheons. And afterwards there is nobody who goes from village to village, like Mahatma Gandhi, to calm the people down and plan campaigns better in future. There is nobody who fasts until they are willing to live together peacefully again.

However, Mahatma Gandhi's message also means strict self-discipline in one's personal life. He persuaded the Indians to burn their clothes imported from Britain. The Indians were to spin their clothes themselves in future. Does Gandhi's teaching me, that we should not wear any clothes made in Thailand, India or Mexico because there textiles are produced by exploited workers? Whom do we support by buying them, if the workers receive only low wages which are hardly enough to live on, whereas the big money lines the pockets of the landowners, merchants and managers? Should not we too grow our food ourselves and do without cheap coffee and bananas? Living in accordance with Gandhi's teaching would be a great sacrifice for us all. We could no longer consume thoughtlessly but would have to live consciously and make do with only what was absolutely necessary.

What is far more important for me today is the way Gandhi treated the untouchables. Gandhi considered the caste system and, in particular, the treatment of the untouchables to be the worst aspect of Hinduism. He championed their cause and nearly died while fasting to improve the quality of their lives. Gandhi called the untouchables Harijans or "children of God".

Who are the untouchables in our country? The groups on the margins of society, such as gypsies, dropouts, the homeless and the handicapped?

According to Gandhi's teaching, we should regard all these people as our equals and treat them as such. We should show them all the same respect and champion their cause, as Gandhi did. This is frequently not the case. We often treat such people as the dregs of our society, as what is left over when we have all passed through the sieve of what is "normal".

In this field too, Mahatma Gandhi's message is of great importance to me. Yet here too I find it hard to live in line with his teaching, to live as he lived. Many young people have no difficulties in their dealings with the handicapped, but many find it hard to regard tramps as equals. "I wouldn't have to sit around in the street." Mahatma Gandhi showed us through his example that it is quite normal to live in such groups on the margins of society and that it is possible to consider everyone to be equal.

My reflections probably show that I have understood Mahatma Gandhi's message, at least in part. Yet I often lose hope when I try to follow his example at least in some respects. After all, we are not called upon to achieve independence for a whole country like Gandhi, but can put his message into practice in parts of our own lives. If I have understood Gandhi correctly, then this is what is important to him: acting in a nonviolent way in one's everyday life and treating all people equally. It is difficult to do. Yet Gandhi gives me courage and hope when he says: "I have not the shadow of a doubt that any man or woman can achieve what I have, ii he or she would make the same effort and cultivate the same hope and faith."