P.O. SEVAGRAM, DIST.WARDHA 442102, MS, INDIA. Phone: 91-7152-284753

FOUNDED BY MAHATMA GANDHI IN 1936

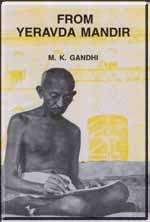

FROM YERAVDA MANDIR [Ashram Observances]

Translated from Gujarati by : Valji Govindji Desai

FROM YERAVDA MANDIR

[Ashram Observances]

Table of Contents

- To The Reader

- Preface

- Truth

- Ahimsa or Love

- Brahmacharya or Chastity

- Control of the Palate

- Non-stealing

- Non-possession or Poverty

- Fearlessness

- Removal of Untouchability

- Bread Labour

- Tolerance, i.e. Equality of Religions-I

- Tolerance, i.e. Equality of Religions-II

- Humility

- Importance of Vows

- Yajna or Sacrifice

- More About Yajna

- Swadeshi

About This Book

Written by : M. K. Gandhi

Translated from Gujarati by : Valji Govindji Desai

First Edition :1,08,000 copies 1932

ISBN : 81-7229-135-3

Printed and Published by : Jitendra T. Desai

Navajivan Mudranalaya,

Ahemadabad-380014

India

© Navajivan Trust, 1932

Download

Chapter 16: Swadeshi

Swadeshi is the law of laws enjoined by the present age. Spiritual laws, like Nature's laws, need no enacting; they are self-acting. But through ignorance or other causes man often neglects or disobeys them. It is then that vows are needed to steady his course. A man who is by temperament a vegetarian need no vow to strengthen his vegetarianism. For the sight of animal food, instead of tempting him, would only excite his disgust. The law of Swadeshi is ingrained in the basic nature of man, but it has today sunk into oblivion. Hence the necessity for the vow of Swadeshi. In its ultimate and spiritual sense, Swadeshi stands for the final emancipation of the soul from her earthly bondage. For this earthly tabernacle is not her natural or permanent abode; it is a hindrance in her onward journey; it stands in the way of her realizing her oneness with all life. A votary of Swadeshi, therefore, in his striving to identify himself with the entire creation, seeks to be emancipated from the bondage of the physical body.

If this interpretation of Swadeshi be correct, then it follows, that its votary will, as a first duty, dedicate himself to the service of his immediate neighbours. This involves exclusion or even sacrifice of the interests of the rest, but the exclusion or the sacrifice would be only in appearance. Pure service of our neighbours can never, from its very nature, result in disservice to those who are far away, but rather the contrary. 'As with the individual, so with the universe' is an unfailing principle, which we would do well to lay to heart.

On the other hand, a man who allows himself to be lured by 'the distant scene,' and runs to the ends of the earth for service, is not only foiled in his ambition, but also fails in his duty towards his neighbours. Take a concrete instance. In the particular place where I live, I have certain persons as my neighbours, some relations and dependants. Naturally, they all feel, as they have a right to, that they have a claim on me, and look to me for help and support. Suppose now I leave them all at once, and set out to serve people in a distant place. My decision would throw my little world of neighbours and dependants out of gear, while my gratuitous knight-errantry would, more likely than not, disturb the atmosphere in the new place. Thus a culpable neglect of my immediate neighbours, and an unintended disservice to the people whom I wish to serve, would be the first fruits of my violation of the principle of Swadeshi.

It is not difficult to multiply such instances. That is why the Gita says : 'It is best to die performing one's own duty or svadharma: paradharma or another's duty is fraught with danger.' Interpreted in terms of one's physical environment, this gives us the law of Swadeshi. What the Gita says with regard to svadharma equally applies to Swadeshi, for Swadeshi is svadharma applied to one's immediate environment.

It is only when the doctrine of Swadeshi is wrongly understood, that mischief results. For instance, it would be a travesty of the doctrine of Swadeshi, if to coddle my family I set about grabbing money by all means fair or foul. The law of Swadeshi requires no more of me than to discharge my legitimate obligations towards my family by just means, and the attempt to do so will reveal to me the universal code of conduct. The practice of Swadeshi can never do harm to any one, and if it does, it is not svadharma but egotism that moves me.

There may arise occasions, when a votary of Swadeshi may be called upon to sacrifice his family at the altar of universal service. Such an act of willing immolation will then constitute the highest service rendered to the family. 'Whosoever saveth his life shall lose it, and whosoever loseth his life for the Lord's sake shall find it' holds good for the family group no less than for the individual. Take another instance. Supposing there is an outbreak of plague in my village, and in trying to serve the victims of the epidemic, I, my wife, and children and all the rest of my family are wiped out of existence; then in inducing those dearest and nearest to join me, I will not have acted as the destroyer of my family, but on the contrary as its truest friend. In Swadeshi there is no room for selfishness; or if there is selfishness in it, it is of the highest type, which is not different form the highest altruism. Swadeshi in its purest form is the acme of universal service.

It was by following this line of argument, that I hit upon Khadi as the necessary and the most important corollary of the principle of Swadeshi in its application to society. 'What is the kind of service, 'I asked myself, 'that the teeming millions of India most need at the present time, that can be easily understood and appreciated by all, that is easy to perform and will at the same time enable the crores of our semi-starved countrymen to live?' and the reply came, that it is the universalizing of Khadi or the spinning-wheel alone, that can fulfil these conditions.

Let no one suppose, that the practice of Swadeshi through Khadi would harm the foreign or Indian mill-owners. A thief, who is weaned from his vice, or is made to return the property that he has stolen, is not harmed thereby. On the contrary, he is the gainer, consciously in the one case, unconsciously in the other. Similarly, if all the opium addicts or drunkards in the world were to shake themselves free from their vice, the canteen keepers or the opium vendors, who would be deprived of their custom, could not be said to be losers. They would be the gainers in the truest sense of the word. The elimination of the wages of sin is never a loss either to the individual concerned or to society; it is pure gain.

It is the greatest delusion to suppose, that the duty of Swadeshi begins and ends with merely spinning some yarn anyhow and wearing Khadi made from it. Khadi is the first indispensable step towards the discharge of Swadeshi dharma to society. But one often meets men, who wear Khadi, while in all other things they indulge their taste for foreign manufactures. Such men cannot be said to be practising Swadeshi. They are simply following the fashion. A votary of Swadeshi will carefully study his environment, and try help his neighbours wherever possible, by giving preference to local manufactures, even if they are of an inferior grade or dearer in price than things manufactured elsewhere. He will try to remedy their defects, but will not because of their defects give them up in favour of foreign manufactures.

But even Swadeshi, like any other good thing, can be ridden to death if it is made a fetish. That is a danger which must be guarded against. To reject foreign manufactures merely because they are foreign, and to go on wasting national time and money in the promotion in one's country of manufactures for which it is not suited would be criminal folly, and a negation of the Swadeshi spirit. A true votary of Swadeshi will never harbour ill-will towards the foreigner: he will not be actuated by antagonism towards anybody on earth. Swadeshism is not a cult of hatred. It is a doctrine of selfless service, that has its roots in the purest ahimsa, i.e. Love.

This note on Swadeshi was not written in Yeravda Mandir in 1930 but outside, after Gandhiji's release in 1931. He did not write it in jail, as he felt he would perhaps be unable to do justice to the subject without encroaching upon the forbidden field of politics. The translation was done by Shri Pyarelal.